This interesting session at the AD:TECH conference in San Francisco featured three different research studies highlighting the way searchers behave. The first study featured an eye tracking study of exactly where searchers look on a search results page, and was the most interesting. The other two studies focused on why searchers click on various links and what traffic analysis reveals about purchases from search.

Gord Hotchkiss, President and CEO of Enquiro, moderated the session, reminding attendees that it’s easy to do search marketing “halfway right” but this session can help you cover the rest of the way. As more and more search marketers get into the game, it becomes important to understand what searchers are thinking and doing to give you the edge.

Greg Edwards, the CTO of Eyetools, collaborated with Enquiro and Did-It.com on an eye tracking study of searchers using Google. First unveiled at the Search Engine Strategies conference in March, the study used 50 people and generated “heatmaps” of the screen areas that more people looked at, with red areas showing more focus of the eyes (with an “X” for a click and a red line for the bottom of the scrolled area of the page). Eye tracking is a very natural environment for visitors (making the results more believable) and answers a question that is critical for search marketers: What are searchers looking at on a result screen? And what are they not looking at? (They won’t click on something they never look at.) This study reveals a “golden triangle” in the upper left of the page where the top two or three organic results are shown, with some additional focus on the top paid search result. Only about 60% of the people scroll below “the fold” (the part of the page that is off the bottom of the screen when first shown).

Greg believes that Google loads up the page so fast that many searchers start out looking at the end of the title of the second search result, which is where the entry box from the search screen is—then they move to the upper left corner. Because of this, the title of the second result may actually have a slight advantage in visibility. (Greg did not say this, but it stands to reason that people using toolbars probably move their eyes to the upper left corner without looking at the middle of the screen first.)

Greg told us that the visibility of the right side results is far lower (30%) than the paid results that are above the organic results (90%) and the top few organic results themselves (80-90%). If there is a “OneBox” (news, book, movie, etc.) at the top of the results, the OneBox is very hot but the top organic results are just as hot—in this case the golden triangle just extends further down the page.

When people return to a search results page, according to Greg, they don’t seem to look at the right-side paid results any more than they did the first time, but they do look further down the search results page for more organic results, with results above the fold still getting a big edge. The full eyetracking study report will be available on May 23.

The next speaker was Akhilesh Bajaj from the University of Tulsa, who studied what motivates a searcher to click on a link on the search results page. The study looked at several factors:

- how closely the title matches what the searcher wants

- the rank of each result

- the reputation of the seller/information source

- how closely the snippet matches the what the searchers wants

The goal was to determine which factors were more important than the others, realizing that there might be differences depending on whether the searchers were informational or transactional (looking to buy) searchers and how “involved” each searcher was in the search scenario. “High” involvement means that it is very important to the searcher that the right information is found, perhaps because of importance to family or health, or because an expensive purchase is being contemplated.

The experiment was designed to use examples of different types as searches with results varying according to the various factors. The study is still being analyzed, but preliminary results are that title match drives 50% of the clicks, with the snippet causing 30% and rank 15%. Surprisingly, the reputation of the content source seemed not to matter, most of the time, which is good news for sellers with unknown brand names. Another unexpected result is that the type of query (informational or transactional) does not have much effect, nor does searcher involvement.

Akhilesh believes that as search engines improve, rank will become more correlated with clicks because they favor results with the title and snippet that best matches the query—so ranking correlates to clicks but are not the cause of the clicks. The cause is that the titles and snippets match better, which was shown by searchers avoiding top-ranked results in the study with bad titles and snippets in the study. So, searchers do not click on results because they are #1 for any reason other than that they are better matches.

Akhilesh says that search marketers should use focus groups to find out what they are searching for, and they should design titles and descriptions that match the best—he believes this will lead to higher clickthrough, based on their study. I think using keyword planning tools and ensuring that your titles and snippets reflect those keywords is just common sense which this study confirms as the correct approach. I don’t think you need to do focus groups—you just need to follow existing best practices.

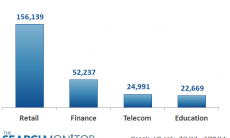

Jarvis Mak, a Director at Nielsen/NetRatings, was up next. Jarvis presented Nielsen’s results from studying search behavior from searchers in their Web panel. Jarvis explained that government and mass merchandisers are the sites that get the highest percentage of visits from search. Universities and current events sites are also quite high in this metric.

Jarvis said that 50% of search sessions had just one search, and 35% of those sessions looked at just one search result screen. As searchers do more and more searches within a session, they are far more likely to look at a second page of search results, and even a third page. These are the distinct minority of searches, but it does show that when searchers are intently searching for something they use more queries and view more results pages.

Google Desktop, Jarvis noted, already has over a million users and 17% are filtering by files and 16% by e-mail. Jarvis believes that Apple’s and Microsoft’s coming move of building desktop search into their operating systems could change searcher’s behavior dramatically—he said that future surveys will look for these changes.

Jarvis found that the top 20% of online consumers account for 88% of all e-Commerce spending, but they actually search a bit less than others. It could be that searchers are actually spending less than non-searchers (which Jarvis believes), but I think that it could easily be that those searchers are buying offline. Jarvis says that 30% of new customers come from search, but that 70% come from existing brand and merchant loyalty or offline drive to Web campaigns. (It is also possible that they once found the Web site from search and have now returned.)

Jarvis believes that search moving to the toolbar and to the desktop is increasing the number of searches, and can help keep per-click prices lower as supply of searches goes up. This is an interesting viewpoint that I have not seen before—given the rise of prices over the last few years, perhaps supply is not increasing as quickly as demand for search paid placement is rising among advertisers.

Search marketers are increasingly interested in studies of searcher behavior, so expect to see more reports like these three in the future.